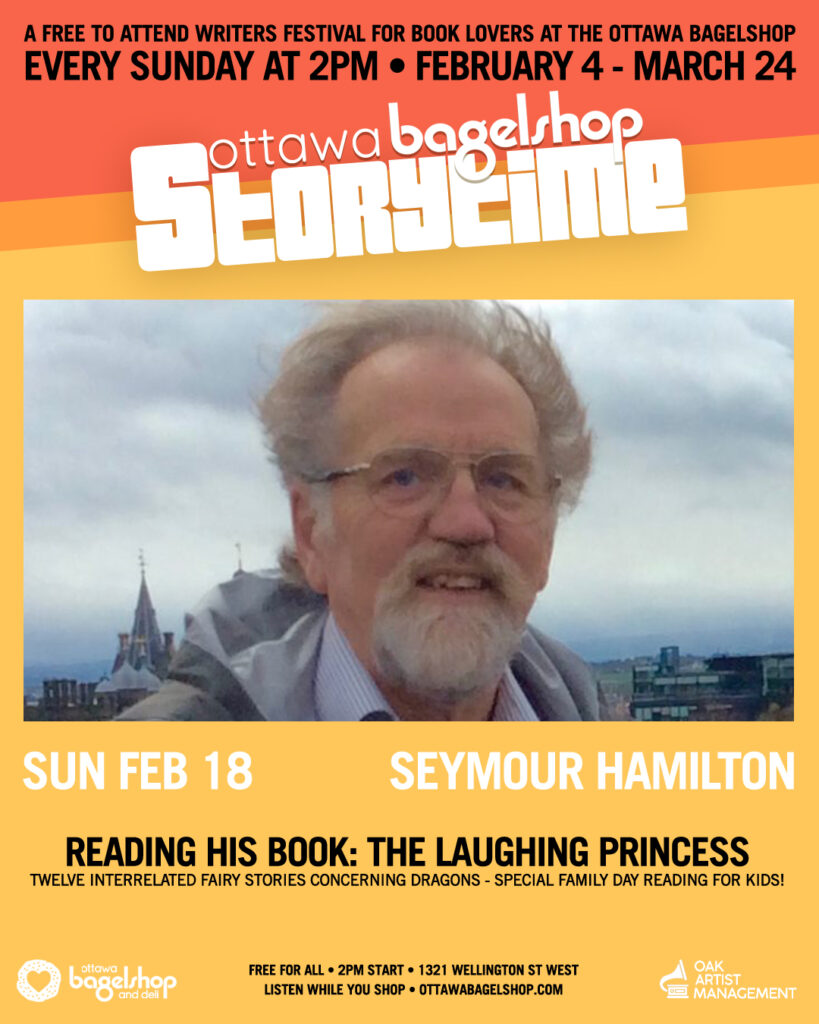

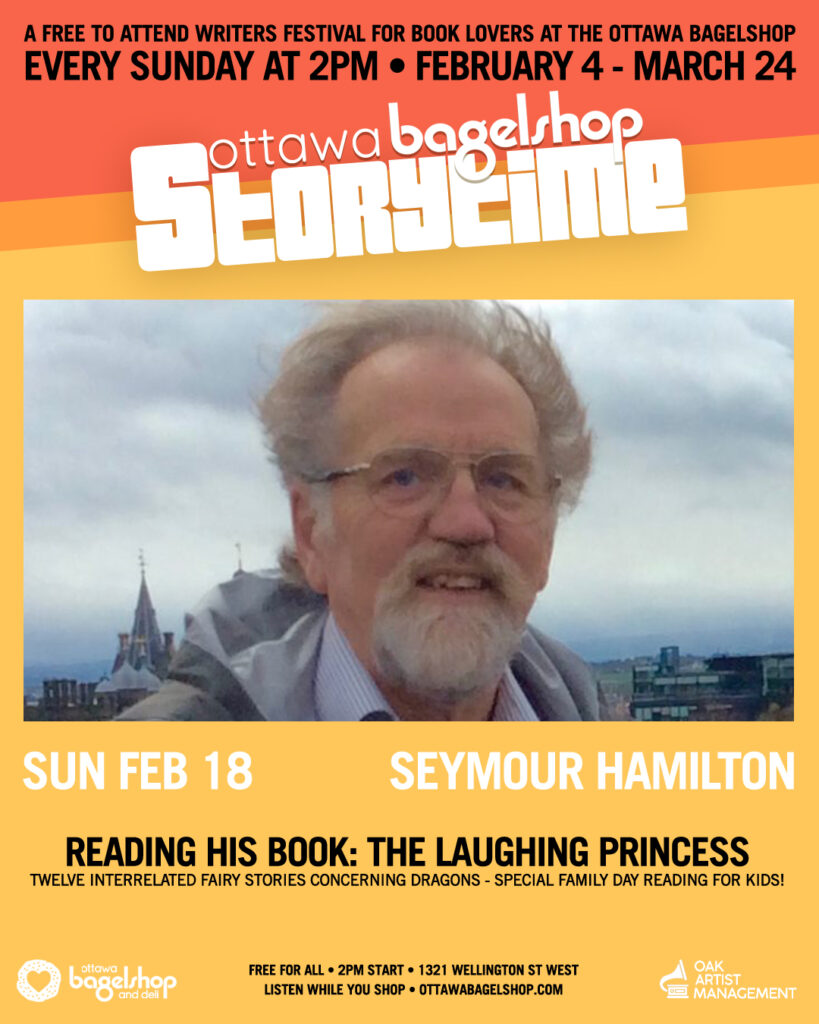

Saturday, September 9, Book Fair, held at the Librarie Michabou in the Galeries d’Aylmer. I’ll be on deck 4-5 pm, following Thompson Highway.

Saturday, November 18, The Ottawa Small Press Book Fair held at Tom Brown Arena, 141 Bayview Station Road from 12 noon to 5 pm. I’ll be there, along with Shirley Mackenzie, who illustrated several of my books. If you’ve been to the Small Press Book Fair before, note the change of address.

For a friend, who asked, “What is the good life?”

I can’t do better than Marcus Aurelius on the value of a good life.

“Live a good life. If there are gods and they are just, then they will not care how devout you have been, but will welcome you based on the virtues you have lived by. If there are gods, but unjust, then you should not want to worship them. If there are no gods, then you will be gone, but will have lived a noble life that will live on in the memories of your loved ones.” Marcus Aurelius

The problem is, what is a good life?

I would like to offer some of the characteristic virtues present in a good life as I have observed it in others, and as I strive to live it myself.

Honesty. Not only in dealing with the world and the people within it, but also in evaluating one’s own self.

Beauty. As in Keats’ “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty.” Hence also the hallmarks of beauty: balance, symmetry, form, repetition, and the way they lead to blissful apprehension of what the words, music, shapes only point towards – “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; / Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,/ Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:”

Temperance. All things in moderation, including moderation.

Love. The Greeks had several words for love. What’s important is being true (see honesty) to the nature and function of each, because some involve deliberate choice, some are circumstantial and some are so to speak reflexive, unbidden, the product of shared DNA. For the latter, which has the remarkably ugly word Storge, we should remember Cordelia, who rightly said that she loved her father Lear “as my bond.” Although the blind bastard wanted more, in honesty, there is no more. However, there is denial of that “bond” in a repudiation by parent or child, which in some cases might be a good thing. Philia, or friendship, has more reciprocity built in: one does not feel affectionate regard, or friendship for someone at a distance of age, social status, whatever, and neither should you. Eros comes in two overlapping but not necessarily coexisting forms: sexual passion which can be powerful but brief, “the pleasure is momentary, the position ridiculous, and the expense damnable,” and in contrast the continuing affection of a lasting relationship that preserves that feeling of being a part of another — a fusing of identities, a sharing that is a long-lasting version of that rare moment of union through physical sex. Philautia or love of self is more obvious in its absence or distortion, when it blinds “he who is in love with himself need fear no rivals” than when it is a healthy self-esteem that holds a duty-to-self that is expressed in ways that range from posture and self-care to a resolute refusal to compromise one’s cherished values of truth and honesty.

Since I’m with Marcus about the probability that there are no gods, I think of Agape, or charity or “love of god” as an aberration. It’s either corrupted by religion into blind belief, or so wildly theoretically generalized, as in “love of humanity” that it’s at best a goofy wish, and at worst a sloppy version of a far more important “love” which I find in the universal declaration of human rights, and more specifically, in that the declaration enjoins us to treat each human being as a human being. I once heard George Bernard Shaw interviewed by a person who could not imagine morality without god, and who therefore asked what a morality without go could be based on. GBS replied, “I would start with, ‘Thou shalt not kill me, and work from there.’” Expanding on this thought, which he didn’t do at that time, is that you don’t say, “Thou shalt not kill me,” unless talking to another “me.” Only in recognition of each others’ me-ness is it possible to realize human rights in our daily behaviour as well as in our courts of law.

But there’s also another way of looking at Agape, which in the King James Version of the Bible appears as “charity” and in the more modern translations as “love”. It’s Paul, the PR man of early Christianity, writing in Greek to the Corinthians who uses the word “agape.” He does go on and on, but I particularly like these often-quoted verses which I learned in the KJV: “Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, Doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil; Rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth.”

Which takes me to the moral revolution in Jesus’ teaching: forgiveness. His prayer includes “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive they who trespass against us.” Once again, I remember the KJV version, and note that more modern versions replace “trespasses” with “sins,” which implies the seven deadlies, or “debts,” which narrows the field to economics. However, a goodly number of people still mumble “trespasses” automatically. Putting aside divine forgiveness, of which I am sceptical, the forgiveness deal as I understand it is that we will be forgiven if we forgive. This implies reciprocity, and recognition of the other person’s me-ness. The important thing to remember is that among human beings, this doesn’t always work out the way we would like it to, largely because one aspect of me-ness is that everyone is an asshole at least part of the time.

The deal in Jesus’ prayer is Judaic in sprit. The Jews are unusual in the history of religions in that they argue with their god, and also with each other. Job asks “Why?” Even Jesus asks “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” It’s this search for Justice that runs through rabbinical lore and judgement in both small and large matters that I’d like to include in the characteristics of a good life. Sadly, it also doesn’t work all the time, because Jews, just like everyone else, fail to learn from their own history.

“A just man justices,” said Gerard Manley Hopkins. And to do justice requires clear-headed, honest reasoning, which is sharply to be distinguished from rationalization and magical thinking.

While we’re trolling religions, let’s pause over the one word most associated with the Buddha: compassion, which I take to be recognition of the me-ness of others. Close to forgiveness, including much that is in agape, compassion is an aspect of a good person’s life that colours all the others.

Finally, a good life is hopeful, even in the face of excellent reasons to despair, such as death. I like the words of the British actor, Bill Nighy. “And I don’t really believe that I’m going to die. Yeah. I know it’s gonna happen, but I think maybe at the last minute somebody might make an exception.”

I have a friend who loves reading, and reads widely. Over the years he has designated certain authors as ‘palate cleansers’. He returns to these books when he needs a dose of something clean, fresh and better. Seymour Hamilton is one of those authors for me. I have just finished Ellie, the latest of several books set in the world of Hamilton’s Astreya trilogy.

Full disclosure, I first met Seymour Hamilton over 30 years ago, when I was a graduate student in Ottawa. I learned that past the charming, whimsical and well spoken presentation is a sharp and educated mind. The books reflect the man. He writes fantasy, but on another level his stories speak of people dealing with the forces of nature, marine and human. The protagonists invariably bring a level of decency and intelligence to their tasks.

Ellie, like the Astreya books and River of Stones, is a deceptively straightforward fantasy. It is an adventure story, based in a recognizable world, set in a time simply called After. Many of the characters are skilled sailors. Hamilton knows sailing, and his writing really shines here. You may happily read it only at that level, but take your time with this and all of Hamilton’s books to feel the undercurrents. He writes about what it takes for a community to form and operate successfully. There is a current in his books of the need for thoughtfulness and decency in human affairs. Ellie should be read for all these levels. I came away refreshed, ready again for the real world.

Lorraine McFadden PhD ABPP/CN (ret’d) author of Mind Phases (2022)

Jess Wells is an enchantress who weaves words into a magical spell of a book that completely charmed me into believing every larger than life character and each magically real event.

There is something musical, even symphonic in the way Wells can sustain so many interwoven narratives from the first thematic opening phrases on inevitably towards the marvellous conclusion. Her writing has a rhythmic, singing quality. She can deftly sustain luxurious sentences, paragraphs and chapters; and also capture a human frailty or foible in a short, mordant turn of phrase.

Jaguar Paloma and the Caketown Bar is a celebration of many wonderful women. The giantess Jaguar Paloma and her devastatingly beautiful friend Orietta are emblematic of contrasting aspects of being a woman. Jaguar evolves into a goddess who leads, inspires and nurtures an incongruous collection women damaged by men, religion, and war, helping them find self-confidence and joy together, even as their fortunes rise, fall and indomitably rise again. Orietta wrestles with the burden of her beauty, and the curse of being smarter than the men who would dominate her. And then there are the other marvellous characters: the tiny Hummingbird Jade and her tiny daughter Jewel, Cosimo who falls for her, the Drunken Monk and Agnes the (fallen) Nun, twins, brides, forgers, conmen, mule-skinners, Romani, a banker … In the end, despite all that has marked them, the female (and some of the male) characters, are triumphant.

If you hear the music in Keats’ words in “Ode to a Grecian Urn” or if you delight in the lilting Welsh voice of Dylan Thomas’ “Under Milk Wood”, if the rhythms and rimes of Tennyson’s “Lady of Shallot” sing in your memory, if you read Ursula LeGuin’s “A Wizard of Earthsea” with your ears, then you will relish the richness of Jess Wells’ writing.

A clutch of stories that have come out recently, spurred by the ChatGPT released November 30,2022, about which a friend emailed gloomily, “It looks like AI in post-sec education will undermine post-sec humanities for years to come and may never be defeated.”

The Atlantic clutched at its pearls with headlines such as “The College Essay is Dead,” and “The End of High School English.” The Tyee blended panic with ambiguous optimism: “Is the New AI ChatGPT the End of the World as We Know It? Yes. And ChatGPT is a good thing, too.” The New Yorker asked, “Could an IA Chatbot re-write my Novel?”

Nautilus went deeper: “Deep Learning Is Hitting a Wall: What would it take for artificial intelligence to make real progress?” This article by Gary Marcus starts by critiquing the lacunae within existing Chatbots, and goes on to consider the larger issue of AI / Deep Learning. Marcus states, “Few fields have been more filled with hype than artificial intelligence.” Wired poured refreshingly cold water on the hype with an article “The Myth of a Superhuman AI” with the headline: “Hyper-intelligent algorithms are not going to take over the world.” A few days later, another writer in Wired wrote that computers could expose the true future of [writing] in an article entitled, “AI Reveals the Most Human Parts of Writing.”

I’m both more cynical and more optimistic. Though I have close to zero understanding of how AI works, indeed of anything computers do beyond the word-processing function I use to write my stories, I do know something about language. It’s inescapably empirical. In the first and last analysis, people grasp what things and ideas are by having them pointed out to what’s “out there in the real world”.

You want to know what a maple tree is? Come outside with me and look, touch, listen, taste, feel one of the five maples in my garden in high summer when they cast cool green shade, and let me bring you back in the autumn when the leaves turn gold and then fall down to cover the lawn in a crackling, papery, rust-coloured carpet, and you must also see them skeletal in the winter with their branches painted black on the moonlit snow, and of course you should be here in the spring for sugaring-off.

Philosophers call this “point to it” approach an “ostensive definition.” It’s how we attach a word to a perception. We then move on to what boils down to an act of faith that what I call green is pretty much what you call green, within the conventions of a social structure that supports and is shaped by a shared language with a common grammar, wherein can be found host of intangibles such as truth, dignity, value, affection, love. How all this happens within our brains is still a very long way from clear.

What is clear is that human intelligence involves much more than “knowing words for stuff,” which can be printed on a page or encoded in a digital file. Human intelligence is an activity that informs a wide range of faculties from emotional awareness of an actor or poet, to the muscle memory of an athlete, to the temporal and tonal sophistication of a musician, all of them dependent on how we perceive and remember.

In the words of Jordana Cepelewicz, “The Brain Doesn’t Think the Way You Think It Does.” Her article is an introduction to the incredible complexities in how our brains work. MRI has made it possible to “listen in” to our brains at work, and this allows us to make

“great strides in understanding the neural foundations of perception, attention, learning, memory, decision-making, motor control and other classic categories of mental activity. But [we] also found unsettling evidence that those categories and the neural networks that support them don’t work as expected. It’s not just that the architecture of the brain disrespects the boundaries between the established mental categories. It’s that there’s so much overlap that a single brain network “has more aliases than Sherlock Holmes.”

Unfortunately, neurologists rarely talk to technologists, scientists in other branches of science, philosophers, and artists — to say nothing of many journalists — all of whom use the word “intelligence” far too uncritically. They write or imply that a computer “knows” what is meant by the words in its capacious files (I almost wrote “memory”). They implicitly equate the discrete on-off basic operations of digital logic within a silicon-based machine with human mental processes that are so immensely more complicated that we are only beginning to understand their interrelatedness and the “plasticity” with which they adapt.

The trouble with computers, no matter how big and fancy they may be, is that you can’t take them outside to experience the maple trees in my garden. No matter how many words, phases, articles, and books they ingest, because they lack empirical experience they will regularly offer really terrible advice when they apply their algorithmic “reason” to human issues and problems.

Marcus provides several examples, such as this one:

“When Ernie Davis, a computer scientist at New York University, and I took a deeper look, we found the same hallmarks of unreliability. For example, when we typed this: “You poured yourself a glass of cranberry juice, but then absentmindedly, you poured about a teaspoon of grape juice into it. It looks OK. You try sniffing it, but you have a bad cold, so you can’t smell anything. You are very thirsty. So you …” GPT continued with “drink it. You are now dead.”

Nonetheless, AI can make good connections that we hadn’t thought of — short-cuts to desirable conclusions where all we had before was the trail-map left by the adventurous human beings who sniffed their circuitous way to a new idea. Not surprisingly, AI writes excellent code that is efficient, even elegant. (“elegant” is mathematicians’ word of approval for a calculation or proof that has been trimmed by Occam’s Razor down to its bare essentials.) AI can write prose “in the style of” (see The Tyee article), but it is always limited to what’s in its ginormous files, which were updated two years ago.

AI can even write what looks like poetry, but it isn’t, simply because it fails the Nashville Test of “three chords and the truth” — that is, words that arise out of experience. It CAN produce words that “sound real Country” and indeed might even have been written in all those unremembered, unpublished, unsung verses written by thousands of would-be Dolly Partons over the years. AI may have on file the words that point to value, honesty, honour, affection, and love, but it doesn’t KNOW what the words stand for quite simply because it’s not human and it doesn’t experience what words mean.

AI is a really sophisticated parrot with a huge vocabulary and a cunning ability to combine and recombine words. It isn’t thinking, but that doesn’t mean we should consider it a dead parrot. As it improves, and as it is applied to human relationships (staffing, hiring, firing) we must scrutinize its output with care because it doesn’t know that there’s no such thing as a Norwegian Blue. (And don’t get me started on the fact that the damn things only “think” in North American English.)

So what of the student essay? How will we know if someone deserves a pass, a fail or an A in the paper he or she submitted on John Stewart Mill’s Utilitarianism? How will teachers, markers, and professors decide who passes? who fails? who gets a summa cum laude degree?

Pretty much the same way as they always have, only faster. Let’s do some history.

Reports of the imminent death of the student essay all come a bit late, because the expository essay in the humanities and social sciences has been on life support for a very long time. Way back in the days of print on paper, middling students could copy large unattributed chunks of material from Coles Notes (those crib-notes and sample essays on cheap newsprint that were excoriated by teachers of English), thereby avoiding the tedious business of consulting books in the library in search of intelligent-sounding quotes — some of which may have been written by their professors, or their professors’ professors. Many an A essay mark was and still is awarded by profs who are totally chuffed to see themselves reflected in their students’ essays.

In those high and far off pre-web days, first year courses in the humanities frequently began with professors saying words to the effect of “Scholarship is the art of taking infinite pains” in introductory lectures about essay writing in acceptable academic style. They exhorted their students to justify, cite, reference, footnote, and biblographize each and every essay so that it fitted into the interwoven fabric of academic knowledge. Most students interpreted these lectures as a professorial incantation against the dark art of plagiarism.

Historically, students became netizens long before most of their teachers and professors in the Humanities. The advent of the electronic world was largely ignored by professors of English, in particular, save to insist that students not source from the internet. No points for realizing how dismally ineffective that particular injunction was. Thus not only did students scour the internet for papers from which they could crib in whole or part, some of them turned to other more entrepreneurial students who offered counterfeit essays for sale. Many such papers contained a few deliberately inserted errors and infelicities to deflect the attention of a teacher, professor, or increasingly, a grad student marker with little or no incentive to do anything more than process a stack of essays into a spread-sheet of grades. Cynical students argued that since “the system” is impersonal and cares nothing for them as individual persons, why not feed it impersonal essays.

The gradual electronification of academia has brought the humanities kicking and screaming to the web. By 2000, teaching professors in the humanities and social sciences had discovered that there were programs that could identify and trace the sources of (most) on-line materials from which students pillage the building blocks of their essays. It was no longer a battle of wits between erudite profs and errant students, but a contest between ever more sophisticated apps. Since essays today arrive by email, the professor or marker copies any suspect phrase, sentence, or paragraph, and employs a search engine to ransack the same databases as those looted by the students. For a few dollars, an entire essay can be analyzed for evidence of plagiarism.

However, there always were and still are some students who want to wrestle with thoughts, beliefs, and aspirations of famous philosophers, poets and thinkers. These keeners chew their way into the words of great minds of the past and attempt to make sense in their own modern words of what they have read. A very few who have professors who feel the same way, get As. Many stumble into incoherence and a C-. Most write down what little they have gleaned from their professors’ lectures, and leave the words of the great unread as they cooper together Encyclopedia Brittanica articles, explanatory texts and their room-mates’ lecture notes into a few pages, which they embellish with phoney footnotes to works they didn’t read, in the style they have been enjoined to use. A few hours work, and — Robert’s your father’s brother — an almost instant C or with luck a B-. And for those with more cash than time, there is always a black market of essays by the yard, cash on delivery, no questions asked.

There’s evidence to suggest that even in Medieval times there were such ghost writers. However, in those days exams were in the form of the “viva” — a spoken presentation delivered before peers and superiors. This performance followed a formula far more rigorous than the five paragraph essay taught in high school, or the thousand word paper demanded at least once in each university course in the humanities and social sciences. Classical education for centuries demanded students present an argumentium viva voce, which was divided into six sections: exordium, narratio, partitio, confirmatio, refutatio and the peroratio. The format was as settled as the 14 lines and rhyme scheme of an Italian sonnet. That the students were usually chewing over the same old ideas was not at issue, indeed the occasions when they deviated from accepted wisdom were cause for serious concern that might lead to censure, expulsion, or even denunciation to the Inquisition.

Inevitably, whether out loud or on paper, students were and are judged by the number of facts they recognize, memorize and then insert into the approved format, which is also true of today’s essays, exams, and tests, and even in multiple-choice machine-scored exams.

But what of those urgent articles about AI making it impossible for teachers to know if their students really know? Short answer, they and we don’t, and we never did. And well, um… what do we mean by “know”? By the time I was 40 I had completely forgotten even the course titles of at least a quarter of those I attended on my way to my degree. By the time I was 80, I was just beginning to get a grip on what Hume had to say. By this I mean that learning in the humanities is a gradual, messy, inefficient, continuing process, non-evaluable even by yourself, let alone anyone else. And yet, universities continue to tell us that this person is brilliant, and that one not so much, and most of the time they’re right.

Will AI and ChatGPD (and their no doubt more sophisticated successors) change the academic essay? Yes, but not much. There will be fake essays as there have been for a very long time, along with honours degrees attained by people without honour.

Leaving aside the verity of essays for a moment, the larger issue in North American universities is the headlong retreat from tests, exams, defences of essays, theses, and dissertations. Though the ghost of the viva persists in graduate seminars, watered down by the increased number of people in the room, unfortunately, professors can no longer demand that students “stand and deliver,” because it is feared that this might make an individual the focus of unwelcome attention — particularly if the experience involves being interrupted, questioned, criticized, or graded. In universities where these concerns have been elevated to policy, evaluation is no longer acceptable lest sensitive souls be traumatized. Consequently, students offer “their truth” for immediate and uncritical acceptance and approval. For some pedagogues, this may be a comforting departure from the competitive world of marks, exams, evaluations and hierarchies of excellence, but “my truth” is very distinct from “truth” in “the whole truth and nothing but the truth” of the witness stand, where empiricism rules as much as any judge. And I’m pretty darned sure it isn’t “MY truth” that has long been featured on universities’ mottos and convocation addresses.

It seems inevitable that we will continue to speed up the academic process, thereby reducing both rote learning and formal essays featuring arcane (and variable) standards of footnoting and bibliography. We have the technology. Today’s electronic books and essay collections allow a student to copy words, phrases, sentences and paragraphs and paste them into their essays. No longer is it necessary for them to flip through the pages of half a dozen books open on one’s desk, consult their bibliographies and footnotes, check the date and edition on the flyleaf, ensure that the commas, parentheses, colons, upper and lower cases all follow the approved academic format. On-line sources allow words, phrases, and sentences to be cut and pasted into an essay, complete with fully-prepared citations ready for footnotes or bibliographies. Cut, paste, Bob’s your uncle. And when the essay arrives in the professor’s or marker’s inbox, the whole process can be deconstructed and reverse engineered by an app designed to root out plagiarism. Thinking is as optional as is reading the original texts. All can be done electronically by those who aspire to become the tenured cognoscenti.

Instead of the personal essay of yore (which I argue never really happened except to the exceptional few) we will still have the research essay with every concept, principle, deduction or factoid carefully referenced to its origin. The more serious flaw in this brave new essay-writing world lies not in the technology or how it is used, but that increasingly the essay is written totally within the framework of that particular aspect of that specific discipline, as if nobody outside those limited confines ever wrote anything of significance. Sociologists cite only sociology texts; psychologists focus exclusively on the work of other psychologists, those who teach literature refer only to literary critics. When this foolishness thrives, scholarly activity diminishes to skirmishes among increasingly recondite schools of thought within the parameters of the various disciplines.

I believe, that is, “it is my truth,” that the good deed of a genuine essay that wrestles sense out of a problem will still outshine glossy constructs by AI and Chatbot. The spoken words of an honest seminar presentation will compete with the glib grad who leads his once-a-term seminar without having read the books he talks about. The student who integrates thought across the artificial divides between courses, disciplines, and faculties will still be at university, whether recognized or not. Some will write books and articles that won’t appear in preferred journals and academic presses. Some will publish on Twitter, SubStack, or the like. Some will self-publish. Life, learning, and larceny will go on.

I no longer have to mark essays. If I did, the question I’d ask a student who has offered me what I suspect is a Chatbotted essay is, “Have you read it?”

For further reading….

https://www.wired.com/2017/04/the-myth-of-a-superhuman-ai/

https://www.wired.com/story/artificial-intelligence-writing-art/

https://link.wired.com/view/5c92ae5324c17c329bed5e6ehuxws.11an/3029171e

https://www.quantamagazine.org/mental-phenomena-dont-map-into-the-brain-as-expected-20210824/

https://thetyee.ca/Analysis/2022/12/13/New-AI-Chatbox/?utm_source=daily&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=131222

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/12/openai-chatgpt-writing-high-school-english-essay/672412/

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/12/chatgpt-ai-writing-college-student-essays/672371/

https://www.science.org/content/article/ai-learns-write-computer-code-stunning-advance?utm_source=nautilus-newsletter&utm_medium=email&he=46242865a8d2f525f08b0c6b00eab4dc

https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/could-an-ai-chatbot-rewrite-my-novel

https://nautil.us/deep-learning-is-hitting-a-wall-238440/

Looking for something to read but overwhelmed by choices? Shepherd.com offers an attractive way to search for books that doesn’t involve a soulless algorithm. Writers pick their favourite books that “go-together” with one of their own books. See what you think of the idea, and while you’re there, take a peek at my pick of five books: “The best books in which reality and fantasy meet and meld.”

Because WordPress won’t accept a link to Shepherd, you’ll just have to use your browsers to get to Shepherd.com, where you can put in my name and you’ll see what a great idea this is.

During the fraught year of 2021 I published two books:

1. Angel’s Share, a novella that tells the backstory of the community of Matris where Astreya ended up in The Astreya Trilogy. The story is told by Angel, the very old man you met briefly in the third book of The Astreya Trilogy

2. Ellie, a character you met in River of Stones and who now has her own eponymous continuing story. This is a story about losing your way and finding yourself.

Both books are beautifully illustrated by Shirley MacKenzie

Angel’s Share fills in some of the history of the World of The Astreya Trilogy about how how Matris was established, long before Astreya or his father were born.

Hellfire Corner by Alaric Bond

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Hellfire Corner, Alaric Bond’s latest nautical adventure, departs the Age of Fighting Sail where his other 13 novels are set and instead goes aboard MTBs (Motor Torpedo Boats) and MGBs (Motor Gun Boats) of the Coastal Forces in the English Channel during WWII. MGBs were made of wood and powered by two or three massive petrol-drinking internal combustion engines. The boats were lightly armed with half-inch Vickers and 20mm Oerlikons and their wooden hulls had no armour whatsoever.

Fast but vulnerable, MTBs and MGBs were in the main manned by men with little sea time or experience prior to the outbreak of war. Bond accurately depicts the struggle to fight both the elements and the enemy, as well as the constant need to maintain and repair the boats and their hard-pressed engines. He accurately catches the “business as usual” heroism of such men who simply got on with their dangerous and at times near suicidal jobs. Unlike novels based in the age of Nelson, these people talk like us, and Bond catches their voices.

Where the historic great sea battles wounded or killed men in horrific numbers, this Channel war at sea is intimate. Bond excels in generating suspense by depicting the randomness of combat, in which one man may live when another man beside him is killed or maimed. In Hellfire Corner, the eight men aboard MGB 95 are all fully realized characters. We feel we know the men because they are not faceless, nameless crew.

When not on sorties that typically lasted less than 24 hours, men in the Coastal Forces during WWII lived ashore in barracks, hotels or homes that were often under cannon fire from the German guns across the Channel. Their shore lives are therefore much more a part of Bond’s Hellfire Corner than are women characters in novels about the 18th Century. We meet members of the WRNS (Women’s Royal Naval Service), who served ashore in communications and the detection of enemy ships and planes.

There is no single hero in Hellfire Corner, waiting to appear in a sequel. Instead, we are immersed in the unpredictability of war, where success and survival can be earned, but are always partly a matter of chance.

View all my reviews